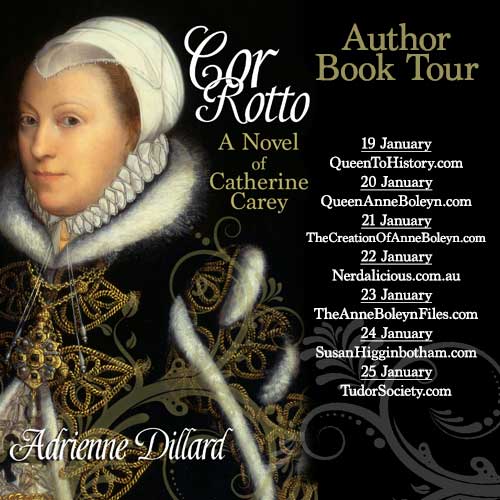

Adrienne Dillard, author of Cor Rotto: A Novel of Catherine Carey, is a graduate with a Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Studies with emphasis in History from Montana State University-Northern.

Adrienne has been an eager student of history for most of her life and has completed in-depth research on the American Revolutionary War time period in American History and the history and sinking of the Titanic. Her senior university capstone paper was on the discrepancies in passenger lists on the ill-fated liner and Adrienne was able to work with Philip Hind of Encyclopedia Titanica for much of her research on that subject.

Cor Rotto: A Novel of Catherine Carey is her first published novel.

Interested in winning a copy of Adrienne’s book? Leave a comment in the comment section for a chance to be drawn and win a free copy!

Jane Rochford, the scheming and voyeuristic housewife, has made an appearance in almost every novel set in Tudor England. Vile and conniving, it was she alone that brought down those infamous Boleyns. Yet, in the same breath, those Boleyns were no victims themselves. Thomas loved to trade his daughters for royal favor and we know what a lascivious fop George was. Anne was the worst of all – in addition to all of her arrogant scheming, she found time to murder. And above all, no one could be worse than Bloody Mary.

The roles seem pretty clear for those that lived in Tudor England. Every Jungian archetype is fulfilled. We have a saint and a sinner; we have a hero and a villain; we have the good and we have the wicked. While these roles may make sense for characterization in any other fictional genre, they have grave consequences for the people represented in historical fiction. Jane, Anne, George and Mary were real people that cannot and should not be contained to these ideals and authors have a responsibility to avoid needlessly tarnishing their reputation.

Based on primary sources of the time, it seems very unlikely that Jane had much to do with the fall of George and Anne Boleyn. Very little seems to have come out of her interrogation and we haven’t any contemporary accounts proving that George and Jane’s marriage was anything but happy; at least happy enough for an arranged marriage. The idea that Anne and Jane despised each other seems to be made out of whole cloth. Never once does Anne mention her dislike for her sister-in-law and on at least one occasion, Jane risked her place at court to help Anne rid herself of a competitor for the King’s affection. The greatest misdeed that Jane can be accused of is the aid she provided to Katherine Howard in her clandestine affair with Thomas Culpeper. But in Jane’s defense, it would have been completely against convention to disobey an order from the queen and as we look deeper into the life of Henry’s fifth queen, it is not even certain that the affair was carried out in the way that it has been traditionally described. Katherine herself has often been painted as either a silly naïve girl or an outright wanton.

Anne seems to suffer from personality disorder. She is either the vile temptress who lures the king away from his rightful wife and plots the poisoning of his pitiful daughter or she is the heroine of the Reformation, a perfect saint among a pit of sinners. The truth of the matter is far more complex than that. Anne was ambitious, yet patient. She had high moral ideals, yet she could be vain. Anne had her sister banished from court, yet she took great care in the upbringing of her nephew and enjoyed a very close kinship with her brother. We know from contemporary accounts that she had quite a temper and had no problem expressing what was on her mind, but we can also rephrase that description to say that she was emotional and had a tendency to stick her foot in her mouth; both very human traits.

George Boleyn was, by all contemporary accounts, a brilliant poet and diplomat. The fact that he rose high so quickly and at such a young age, even before his sister was queen, speaks highly of his capabilities. Records indicate that he was well-liked by his peers and may have even been regarded as an unfortunate victim of his sister’s downfall. The idea that he was a libertine has no basis in fact, yet it seems to be the reputation that follows him the most. George was far from perfect though, he was often arrogant and frivolous with his money. He was known to charm the ladies of the court and his humor was not always appreciated.

In Cor Rotto, I tried very hard to stay away from the molds that have formed over the years. There are no heroes or villains. Though Catherine is very kind and pragmatic she can also behave childishly and is often wracked with self-doubt and pity. Francis deals harsh judgment upon those who don’t conform to his moral ideals, but he is a loving husband and father. He is also loyal to his friends even when others would abandon them. In Queen Mary, we see that while deeply flawed and easily manipulated, she can show kindness and mercy. She is not entirely to blame for the horrors carried out under her reign.

It is my hope that readers will see the humanity that lies within each one of these complex individuals. Everyday life is certainly different than it was five centuries ago, but the complexity of the human spirit remains.

Blurb from Cor Rotto: A Novel of Catherine Carey

The dream was always the same … the scaffold before me. I stared on in horror as the sword sliced my aunt’s head from her swan-like neck. The executioner raised her severed head into the air by its long chestnut locks. The last thing I remembered before my world turned black was my own scream.

Fifteen year-old Catherine Carey has been dreaming the same dream for three years, since the bloody execution of her aunt Queen Anne Boleyn. Her only comfort is that she and her family are safe in Calais, away from the intrigues of Henry VIII’s court. But now Catherine has been chosen to serve Henry VIII’s new wife, Queen Anne of Cleves.

Just before she sets off for England, she learns the family secret: the true identity of her father, a man she considers to be a monster and a man she will shortly meet.

Purchase The Creation of Anne Boleyn: A New Look at England's Most Notorious Queen (US)

Purchase The Creation of Anne Boleyn: A New Look at England's Most Notorious Queen (US)