A 19th century engraving titled "Anne Boleyn Receiving Proof of Henry's Passion for Jane Seymour"

Do note cite, quote, copy, or distribute without consent of author: Bordo@uky.edu.

Hilary Mantel’s prize-winning Wolf Hall ends portentously, with Cromwell and Henry about to embark, in September 1535, on a progress that would include a stop at Wolf Hall, home of John Seymour and his family. Mantel chose the ending (and the title of her book), we can safely speculate, to mark the beginning of Anne’s final and fatal twist of bad luck, with Henry catching sight of Jane, John Seymour’s daughter.

Mantel’s is not the first or last depiction to imagine such a meeting—among the most well known, the BBC’s Six Wives of Henry VIII and Showtimes’ Tudors. It’s one of those fictions that have endured across the centuries in our collective narrative of Anne’s fall. But it’s very unlikely either that Henry saw Jane for the first time at Wolf Hall, for Jane had been one of Katherine of Aragon’s ladies, and then returned to court to be part of Anne Boleyn’s entourage in 1534, well before the Wolf Hall progress, or that anything momentous passed between them on that visit. For one thing, Anne was with Henry. For another, we don’t even know for sure if Jane was there.

The first clear mention of a relationship between Henry and Jane occurs in Chapuys’ February 17 (1536) letter to Charles, in which he wrote that Anne’s inability to bear male children was due to her “defective constitution,” and that “the real cause” of her miscarriage of January 29 may have been the King’s “behavior toward a damsel of the Court, named Miss Seymour, to whom he has latterly made very valuable presents.”

February 1536. If the king had begun seriously pursuing Jane in September of 1535, it’s highly unlikely that the gossip-hungry Chapuys—always ready to report any decline in Henry’s feelings for Anne—would have waited six months to report it to Charles. It makes for a good story: King’s declining passion for his first wife, her escalating jealousy and shrewishness, setting the stage for a tipping-point meeting between Henry and sweet, submissive Jane, providing the spark which turned the tinder of his marriage to Anne into a roaring, destructive fire. But in fact, there seems to have been no single factor—certainly not Jane Seymour–that brought about the disastrous events of April-May 1536, but a combustion of court atmospherics, political maneuvering, and sheer bad luck. What turned the cherished, hotly pursued consort into the lady in the tower, awaiting her execution, did not belong primarily to the realm of emotions, but to the gathering of a “perfect storm” of political, personal, and biological events, the absence of any one of which might have resulted in things turning out very differently for Anne.

The atmospherics included a strong political/religious “wing” of anti-Anne sentiment that was a powerful obstacle in the way of Anne’s acceptance by the (still largely Catholic) English people. In gaining that acceptance—and with it some protection from the winds of shifting politics—Anne already had several strikes against her. She had supplanted a beloved queen. She was rumored to be “haughty” and suspiciously “French”–and even worse than that, a vocal, intellectual, “interfering” woman. Even those who shared her religious views, like Cromwell, had no scruples about spreading nasty rumors when it suited their purposes. For Anne’s reputation as a woman who simply would not behave as she should had created an atmosphere that did not incline men to be her protectors, but rather freed them to take the gloves off when fighting with her. “Had she been gracious and modest,” writes 19th century commentator James Froude, “she might have partially overcome the prejudice against her.” (P 384). “Gracious and modest” seem like laudable qualities. But what they meant in the context of the times and why Anne could never play the part is laid bare by David Loades: “Anne could not pretend to be a fool or a nonentity, and the self-effacement customary in a royal consort did not suit her style at all…In many ways her sharpness of perception and readiness of wit made her more suitable for the council chamber than for the boudoir.” (69) But women did not belong in the council chamber.

By 1536, Henry was also well aware that public opinion, especially after the executions of Bishop Fisher and Thomas More (for refusing to take the oath declaring Henry Supreme Head of the Church of England) was not exactly riding in his favor.

Besides anger over Fisher and More, who were generally admired, there was a growing public sentiment over the mistreatment of Katherine and Princess Mary, who Henry kept separated from each other, and treated like discarded limbs. The abuse of Mary was especially acute, as she was forced to wait on her younger sister Elizabeth, and allowed no audience with the King, who had formerly been an affectionate father, so long as she refused to acknowledge Anne as Queen. This she would not do, not even after Anne had personally offered her friendship and a home at court, on that one condition. Despite a huge amount of evidence that Henry was in a rage over his daughter’s “obstinacy” and hardly required any goading to punish and humiliate her, Chapuys blamed her mistreatment entirely on Anne, whom he believed turned the King against Mary, and did all that he could to insure that every other person who would listen to him saw it that way.

Even those who knew better, like Thomas Cromwell, realized that blaming the King for Mary’s mistreatment could create a huge public relations disaster and encouraged Chapuys in his Anne-blaming. As early as October of 1534, Chapuys had met with Cromwell, who reassured Chapuys of Henry’s “paternal affection” for Mary and claimed that he “loved her 100 times more than his last born” and that he and Chapuys ought to do all that they could to “soften and mend all matter relating to her,” for “in time everything would be set to rights.” Although I am often skeptical of Chapuys’ second and third-hand “intelligence,” the manipulative, self-serving speech he attributes to Cromwell has, to my ears, the ring of truth. In it, Cromwell takes credit for paving the way to smoother relations between Henry and Charles, and assures Chapuys that the only obstacle standing between a renewed friendship between England and Spain was a “satisfactory settlement of all complaints” held by Mary and Katherine. He ended, Chapuys reports, ”by saying in passing that it was perfectly true that great union and friendship existed now between France and England, but that I could guess the cause of it. He did not say more on this subject. Your Majesty, by your great wisdom, will be able to judge what Cromwell’s last words meant.”

Of course, the “cause” that was implied here was Anne—who now was “hinted” by Cromwell as standing between the repair of relations between England and Spain, and in a double way: First, because she was known to be a Francophile, who had been raised to be “more French than English,” but more important, because she was the obstacle standing in the way of reaching a “satisfactory settlement of all complaints” by Katherine and Mary. Chapuys also took Cromwell as hinting “that there was some appearance of the King changing his love.” He wasn’t sure whether to take this seriously—for Cromwell was quite capable of dissembling when it suited his purposes—but what seems crystal clear is that Cromwell was buttering Chapuys up, in the interests of Henry’s PR and future good relations with Charles, and that Anne was already being used by him to take the heat off Henry.

Why would Cromwell, who shared Anne’s religious proclivities, want to stir up the anti-Anne pot with Chapuys and Charles? After all, he had been chief engineer of the break with Rome and, as a reformist himself, had been Anne’s strongest ally at the start of her relationship with Henry. At one point, it was generally believed that Anne had him “in her pocket” (or, as Chapuys later put it, was “Anne’s right hand.”) What had happened? At this point, nothing of grave significance. But the two had a serious break brewing. For although they may have shared the same “theory” of reform (although we don’t know for sure, as what became British Protestantism was only just evolving) they disagreed sharply on what should be done with the spoils of disbanded churches and monasteries. From the beginning of his ascent to power—and among the reasons why he was able to keep the favor of the nobility, even after Wolsey was deposed—Cromwell “actively assisted the King in diverting revenues from the suppressed monasteries, originally granted to Wolsey’s two colleges, to the purses of Henry’s cronies at court.” (43, Hutchinson) Anne, in contrast, favored using the funds to set up educational and charitable institutions, and was shocked to learn that the money was being diverted for private use. This difference between them would not explode until April of 1536, but it seems that in sidling up to Chapuys, Cromwell was already preparing for the possibility that it might come to a show-down resulting in his own fall from favor, and he was seeking alliance with Chapuys to prepare for the need for a strike against Anne.

Cromwell was aware that developing a friendship with Chapuys was risky, but assessing the situation at the time, he wasn’t overly concerned. In June of 1535 he told Chapuys that if Anne knew how close he and Chapuys were, she would see Cromwell’s head off his shoulders. At the time, Cromwell shrugged it off, telling Chapuys that “I trust so much on my master that I fancy she cannot do me any harm.” (Lion’s Court, 384) But the differences between Anne and Cromwell were escalating—not just over the use of confiscated money but also over international alliances (Anne favored France, while Cromwell was beginning to lean toward some kind of accommodation with Charles) and the mere fact that Cromwell, in 1535, was already assessing his security relative to Anne’s displeasure with him suggests that he was aware that she could, under the right circumstances, be a danger to him—and was making preparations.

Cromwell also undoubtedly became aware, in the fall of that year, that a new family was rising in the king’s favor: The Seymours. Edward Seymour, who had hosted a visit from Henry to Wolf Hall in September, was becoming a special favorite. Henry had always enjoyed the company of vital, masculine, young men (“thrusting, acquisitive and ambitious” is how Wilson describes them-p. 386, In The Lion’s Court), and as his own athleticism and sense of masculine potency declined, hobbled by leg ulcers and increasing obesity, he may have begun to live vicariously through them, “unconsciously sucking new life from their physical and mental vigor.” (Wilson, p. 385) By 1535, Seymour’s circle—John Dudley, Thomas Wriosthesley, and Ralph Sadler—had come to serve this function for Henry. They were also courting Cromwell, who they rightly saw as having the king’s ear and who was seemingly, at this point, the architect of England’s future. They hated the Boleyns. And Edward Seymour had a sister. Conveniently, she was in startling contrast to Anne: “fair, not dark; younger by seven or eight years; gentle rather than abrasive; of no great wit, against a mistress of repartee; a model of female self-effacement against a self-made woman.” (Ives, 302)

The gentle, self-effacing sister, however, probably would not have amounted to anything of significance were it not for the momentous events of January 1536. On January 7, Katherine of Aragon had died, most likely of cancer of the heart (a real illness, but an apt bodily metaphor as well.) At the time, it was an enormous relief to both Anne and Henry. For Anne, it meant that at last she was the only Queen of England. And both of them hoped that Katherine’s death, removing the chief reason for the Emperor’s breach with Henry, would repair relations with Charles and tip the balance in England’s favor vis a vis Francis (who now would have to court Henry, in order to be sure England did not ally him with Charles.) “The next day”, Ives reports, “the king and queen appeared in joyful yellow from top to toe, and Elizabeth was triumphantly paraded to church. After dinner Henry went down to the Great Hall, where the ladies of the court were dancing, with his sixteen month old daughter in his arms, showing her off to one and another.” Whether or not their yellow clothing was to mark their joy, as Ives says, or a sign of respect for the dead has been much debated. But whatever the meaning of the color of their clothing, at this point, neither had a political reason to mourn Katherine’s death—and Henry, over the years of battle with Katherine, seems to have lost any trace of affection for her.

Chapuys, however, was horrified by their reaction, grief-stricken at having lost his longtime friend, whom he had comforted and championed over the years, and quickly began spreading rumors that Katherine had been poisoned by Anne. But good news was to come a bit later that month, when Chapuys reported, third-hand as usual, that one of the King’s “principal courtiers” said that the King had confessed to another lady and her husband that “he had been seduced and forced into this second marriage by means of sortileges and charms, and that, owing to that, he held it as null. God (he said) had well shown his displeasure at it by denying him male children. He, therefore, considered that he could take a third wife, which he said he wished to do.” Even Chapuys, ever alert to promising signs that Anne would be supplanted, finds this report “incredible.” Anne was in her final month of pregnancy; how could the King be sure that God would not bless the marriage with a male heir this time around? Was someone whispering in Henry’s ear, planting suggestions about Anne?

It seems that this is exactly what was happening. By April 1st, Chapuys was writing to the Emperor, informing him that the king was “paying court” to Edward’s sister Jane, and that he had “heard” (from the Marchioness of Exeter) that Jane had been “well tutored and warned by those among this King’s couriers who hate the concubine, telling her not in any wise to give in to the King’s fancy unless he makes her his Queen, upon which the damsel is quite resolved. She has likewise been advised to tell the King frankly, and without reserve, how much his subjects abominate the marriage contracted with the concubine, and that not one considers it legitimate.” The Marchioness also requested, at this time, that Chapuys himself aid in whatever way he can in the “meritorious work” of removing Anne and thus, not only protecting Princess Mary from Anne’s evil plotting and ridding the country of the “heretical doctrines and practices” of “Lutheranism,” but “clearing the King from the taint of a most abominable and adulterous marriage.”

In the short space between Katherine’s death and Henry’s open courting of Jane, two events that proved disastrous to Anne had occurred. These events were far more decisive to her future than any developing attraction of Henry for Jane. First, on January 24, Henry had a bad jousting accident, which left him unconscious for two hours, and undoubtedly stirred up his anxiety about his own diminishing physical competence and reminded him of his mortality—something he had been trying to avoid all his life through a hypochondria bordering on obsession. Then, on January 29th, Anne miscarried. Although it was probably too early in the pregnancy for attendants to determine the sex of the child, which was described by Chapuys as a “shapeless mass of flesh,” it was reported by both Chapuys and Wriosthesley that it had been a male. This was a “huge psychological blow” to Henry. We only have Chapuys to rely on for details—“I see that God will not give me male children” he reports Henry as saying, and then ominously telling Anne that he would “speak to her” once she was up—but whether the quote is accurate or not, it makes sense that the loss of a potential heir, especially after at least one other miscarriage and his own recent brush with death, would have affected Henry deeply. Anne, on her part, was distraught. She appealed to Henry, telling him that the miscarriage was the result of shock over his accident, which is not improbable, although Chapuys, as mentioned earlier, believed it to be cause by her “defective constitution” and jealousy over Jane, to whom the king had been sending gifts, just as he had done in the early days of his courtship of Anne.

Whether through coaching or inspiration of her own, Jane refused the king’s gifts, saying that her greatest treasure was her honor, and that she would accept sovereigns from him “once God had sent her a good match.” She may have not been of “great wit” but she (or her brother) knew that this would increase Henry’s ardor. The refusal of sovereigns happened, however, only after Anne’s miscarriage, suggesting this was an event that emboldened Jane and her supporters. For if Anne had produced a living son, all the rumblings about Anne, both at court and among the people, all the conniving of the Seymours, would have crashed against a brick wall. But it was Anne’s disastrous luck that not only did she miscarry, but that it happened after Katherine died. Initially, that death had been a cause for celebration. What Anne did not take into account (or perhaps did, but had no reason to consider probable at this point) was that with Katherine’s death, Henry could have his marriage to Anne annulled, or invalidated in some other way, without having to deal with Katherine’s claims to the throne. Fatally and without precedent, it was “the some other way” that prevailed.

There are a number of theories as to what allowed the unthinkable—the state-ordered execution of a Queen—to happen. One theory, first advanced by Retha Warnicke and adopted by a number of novels and media depictions, is that the miscarried fetus was grossly deformed, which led to suspicions of witchcraft. If Henry truly believed that Anne was guilty of witch-craft—which of course was a possibility in those times—he would have virtually no choice but to destroy her, as with anyone in league with Satan. But although Henry complained, at one point, that he had been bewitched by Anne, that was a notion that, as in our own time, was freely bandied about in very loose, metaphorical manner. It could mean simply “overcome beyond rationality by her charms” (as Chapuys himself means it early in Anne and Henry’s relationship, when he complained that the “accursed lady has so enchanted and bewitched him that he will not dare to do anything against her will.”) Moreover, none of the charges later leveled against Anne involved witchcraft, and there is no evidence that the fetus was deformed.

Another theory, which Alison Weir puts forward in The Six Wives of Henry VIII but revises in The Lady in the Tower, is that Henry, fed up with Anne, newly enamored of Jane, and eager “to rid himself” of his second wife but not knowing how, eagerly embraced Cromwell’s suggestion, in April, that he had information that Anne had engaged in adultery. “Spurred by his passion for Jane, his need of the Spanish alliance, and his desire for vengeance against Anne, who had promised so much and failed to deliver,” he “accepted the allegations at face value, merely asking Cromwell to find evidence to support them.” (309) But even if we accept the idea that Henry would cynically encourage a plot designed to lead to Anne’s execution, and despite his flirtation with Jane and disappointment over the miscarriage, Henry did not behave, before Cromwell put the allegations before him, like someone looking to end his marriage. Whatever he was feeling about Anne, recognition of his supremacy was still entwined with her, and even after the miscarriage, he was still working for imperial recognition of his marriage to “his beloved wife” Anne. With Katherine gone, it seemed a real possibility. And in fact, in March, the emperor offered, in return for the legitimation of Mary, imperial support for “the continuance of this last matrimony or otherwise,” as Henry wished (Ives 312). The deal didn’t work out, due to Henry’s refusal to acknowledge that anything about his first marriage—including Mary—was legitimate. He was utterly committed to maintaining his own absolute right to the organization of his domestic affairs, and that meant both recognition of Anne as lawful wife and Mary as bastard.

Most scholars nowadays (with a couple of exceptions whom I’ll discuss elsewhere) believe, following Eric Ives, that Thomas Cromwell orchestrated the plot against Anne, without Henry’s instigation or encouragement. Things had been brewing dangerously between him and Anne for some time, and by April, she probably knew that he had become friends with the Seymours and had also been sidling up to Chapuys. On April 2, Anne had dared to make a public declaration of her opposition to his policies by approving of a sermon written by her almoner, John Skip, in which he compared Cromwell to Haman, the evil, Old Testament councilor. The specific spur for the sermon was proposed legislation to confiscate the wealth of smaller monasteries, which was awaiting Henry’s consent and against which Anne was trying to generate public sentiment. But by then, the enmity between Anne and Cromwell had become more global than one piece of legislation. Still, as he told Chapuys, Cromwell felt more or less secure in Henry’s favor until a crucial meeting between the Ambassador and the King on April 18th, in which Henry, who had seemed to be in favor of the reconciliation with Rome which Cromwell had been negotiating with Chapuys, now revealed his true hand, and refused any negotiation that included recognition of his first marriage and Mary’s inclusion in the line of succession. Cromwell was aghast at Henry’s stubbornness, as he had been working hard toward the rapprochement with the emperor, burned his bridges with France, and (because of his relationship with Chapuys) with Anne and her faction as well. Earlier in the day, it had seemed that some kind of warming between Chapuys and Anne was being orchestrated. Chapuys had been invited to visit Anne and kiss her hand—which he declined to do—then, was obliged to bow to her when she was thrust in his path during church services. Later, at dinner, Anne loudly made remarks critical of France, which were carried back to Chapuys. But when after dinner, Henry took Chapuys to a window enclosure in his own room for a private discussion, he made it clear that he wouldn’t give.

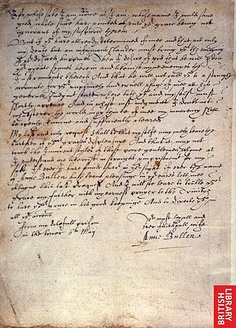

“Far from the issue of April 1536 being ‘When will Anne go and how?’” Ives writes, “Henry was exploiting his second marriage to force Europe to accept that he had been right all along.” (315) Cromwell was furious, humiliated, and fearful that he had unexpectedly found himself on the wrong side of Henry’s plans. In a letter to Charles, Chapuys wrote about the April 18 meeting, and what he wrote suggests that what was already on high heat between Cromwell and Anne was about to boil over. Chapuys reports that one reason why he would not “kiss or speak to the Concubine” and “refused to visit her until I had spoken to the King,” was because he had been told by Cromwell that the “she devil” (Chapuys’ appellation, not Cromwell’s) “was not in favor with the King” and that “I should do well to wait till I had spoken to the King.” Chapuys, London, 24 April 1536 (Venice Archives).

With the king still pushing for her recognition, Anne must have felt deceptively safe. On April 24, Henry writes a letter to Richard Pate, his ambassador in Rome, and to Gardiner and Wallop, his envoys in France, referring to “the likelihood and appearance that God will send us heirs male [by] our most dear and most entirely beloved wife, the Queen.” But something has already begun to seem wrong to Anne, who seeks out her chaplain, Matthew Parker on the 26th, and asks him to take care of Elizabeth, should anything happen to her. And in the days that follow, Chapuys is clearly (and gleefully) aware that plots are being hatched against Anne. He writes to Charles that there is much covert discussion, at court, as to whether or not “the King could or could not abandon the said concubine,” and that Nicholas Carew is “daily conspiring” against Anne, “trying to convince Miss Seymour and her friends to accomplish her ruin. Indeed, only four days ago the said Carew and certain gentlemen of the King’s chamber sent word to the Princess to take courage, for very shortly her rival would be dismissed.” When the bishop of London, John Stokesley, expressed skepticism, “knowing well the King’s fickleness” and fearful that should Anne be restored to favor, he would be in danger, Chapuys reassures him that the King “would certainly desert his concubine.”

In fact, after the April 18th meeting, Cromwell, claiming illness, had gone underground to begin an intense “investigation” into Anne’s conduct. On April 23, he emerged, and had an audience with Henry. We have no record of what was said. But many scholars believe that the illness was a ruse, that during his retreat he carefully plotted Anne’s downfall, and that what he told the king on April 23 were the deadly rumors about Anne that eventually led to her arrest and trial. The king, however—perhaps dissembling for public consumption, or perhaps unconvinced by what Cromwell has told him—was still planning to take Anne with him to Calais on May 4th, after the May Day jousts, and was still pressing Charles to acknowledge the validity of his marriage to Anne. Then, on April 30th, Cromwell and his colleagues lay all the charges before Henry, and court musician Mark Smeaton is arrested.

Anne had no idea that Cromwell and Henry, that day, were meeting to discuss the “evidence” that Anne had engaged in multiple adulteries and acts of treason. That evening, while Smeaton was being interrogated (and probably tortured), there was even a ball at court at which “the King treated Anne as normal.” He may have been awaiting Smeaton’s confession, which didn’t come for 24 hours, to feel fully justified in abandoning the show of dutiful husband. Although we don’t know for sure what message was given to Henry during the May Day tournaments, it was probably word of Smeaton’s confession, for he immediately got up and left. Anne, who had been sitting at his side, would never see him again; the very next day, as her dinner was being served to her, she was arrested and conducted to the Tower.

The following article is a guest post by Kyra Kramer, author of Blood Will Tell: A Medical Explanation for the Tyranny of Henry VIII.

The following article is a guest post by Kyra Kramer, author of Blood Will Tell: A Medical Explanation for the Tyranny of Henry VIII.

Purchase The Creation of Anne Boleyn: A New Look at England's Most Notorious Queen (US)

Purchase The Creation of Anne Boleyn: A New Look at England's Most Notorious Queen (US)