By Susan Bordo, author of The Creation of Anne Boleyn

From the time she was taken to the Tower, Anne’s moods, according to Constable Kingston, vacillated wildly, from resignation to hope to anxiety. She had always had a wicked sense of humor, and no irony was ever lost on her. When taken to the Tower, she had asked, “Master Kingston, shall I die without justice?” He replied, “The poorest subject the king hath, had justice.” Hearing this, despite her fear, Anne laughed. She was too sophisticated and savvy about the dispensing of royal power to swallow the official PR. Even the night before her execution, her sense of irony held as she wryly remarked that her enemies would remember her as “la Royne Anne Sans Tete” But until very near the end, she also seized on any glimmer of hope. She was the queen, after all, and no one in England had ever executed a queen. Isabella of Angouleme and Isabella of France, both married to English kings, had been adulterous, but only their lovers were executed. Even those who had been involved in acts of treason—the most famous of all being Eleanor of Aquitaine, who almost succeeded in toppling Henry II from his throne—at most were put under house arrest. It was almost unthinkable to Anne that Henry would have her put to death. But so, too, was her imprisonment, which had come so suddenly, and seemingly without reason. The strangeness of what was happening to her must have been at times impossible for her to assimilate. Just a few short months before, she had been pregnant. Just a few weeks before, Henry had been insisting that the Spanish Emperor acknowledge the legitimacy of their marriage. Now she was in the Tower, condemned to death. Her fortunes had turned around so swiftly and extremely, it must have been difficult to keep a steady grip

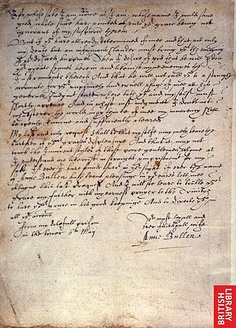

On May 5, Anne asked Constable Kingston to “bear a letter from me to Master Secretary.” Kingston then said to her: “Madam, tell it me by word of mouth and I will do it.” Anne thanked him, and after that we hear no more of it in Kingston’s reports, so we don’t know if the letter was written, dictated, or even ever was composed. But one was found among Cromwell’s papers, dated May 6th, apparently undelivered. The handwriting doesn’t correspond exactly (although it is not radically dissimilar) to Anne’s other letters, but it could easily have been transcribed by someone else or written in Anne’s own hand, which could have been altered by the distress of the situation. It begins with a statement that is so startlingly precise in its depiction of Anne’s state of mind at the time, that it’s hard to imagine anyone else, in the decades following her death, writing it:

Your Grace’s displeasure and my imprisonment are things so strange to me, that what to write, or what to excuse, I am altogether ignorant. Whereas you send to me (willing me to confess a truth and so obtain your favour), by such a one, whom you know to me mine ancient professed enemy [Cromwell]; I no sooner received this message by him, than I rightly conceived your meaning; and if as you say, confessing a truth indeed my procure my safety, I shall, with willingness and duty, perform your command.

But let not your grace ever imagine your poor wife will ever be brought to acknowledge a fault, where not so much as a thought ever proceeded. And to speak a truth, never a prince had a wife more loyal in all duty, and in all true affection, than you have ever found in Anne Bolen – with which name and place I could willingly have contented myself if God and your grace’s pleasure had so been pleased. Neither did I at any time so far forget myself in my exaltation, or received queenship, but I always looked for such alteration as I now find; for the ground of my preferment being on no surer foundation than your grace’s fancy, the least alteration was fit and sufficient (I knew) to draw that fancy to some other subject.

You have chosen me from a low estate to be your queen and companion, far beyond my just desert or desire; if then you found me worthy of such honour, good your grace, let not any light fancy or bad counsel of my enemies withdraw your princely favour from me, neither let that stain – that unworthy stain – of a disloyal heart toward your good grace ever cast so foul a blot on me and on the infant princess, your daughter [Elizabeth].

Try me, good king, but let me have a lawful trial, and let not my sworn enemies sit as my accusers and as my judges; yea, let me receive an open trial, for my truth shall fear no open shames; then shall you see either mine innocency cleared, your suspicions and conscience satisfied, the ignominy and slander of the world stopped, or my guilt openly declared. So that whatever God and you may determine of, your grace may be at liberty, both before God and man, not only to execute worthy punishment on me, as an unfaithful wife, but to follow your affection already settled on that party [Anne knew of Henry’s affection for Jane Seymour], for whose sake I am now as I am; whose name I could some good while since, have pointed unto: Your Grace being not ignorant of my suspicions therein.

But if you have already determined of me, and that not only my death, but an infamous slander, must bring you to the joying of your desired happiness, then I desire of God that He will pardon your great sin herein, and, likewise, my enemies, the instruments thereof, and that he will not call you to a strait account for your unprincely and cruel usage of me at his general judgment-seat, where both you and myself must shortly appear; and in whose just judgment, I doubt not (whatsoever the world think of me) mine innocency shall be openly known and sufficiently cleared.

My last and only request shall be, that myself may only bear the burden of your grace’s displeasure, and that it may not touch the innocent souls of those poor gentlemen, whom, as I understand, are likewise in strait imprisonment for my sake.

If ever I have found favour in your site – if ever the name of Anne Bulen have been pleasing in your ears – then let me obtain this request; and so I will leave to trouble your grace no further: with mine earnest prayers to the Trinity to have your grace in his good keeping, and to direct you in all your actions.

From my doleful prison in the Tower, the 6th of May.

Ann Bulen

Most of Anne’s modern biographers believe this letter to be a forgery, in part because it is so daringly accusatory of Henry and in part because the “style” is not like Anne’s. “Its ‘elegance’,” writes Ives, “has always inspired suspicion.” Well, not always. Henry Ellis and other nineteenth-century commentators believed it was authentic. And the “style” argument is an odd one, because we have so few existing letters of Anne’s and they are such business-like affairs, that it’s hard to see how anyone could determine a “style” from them. If Henry had saved her responses to his love letters, we might have a better idea of what Anne was like as a writer, but they were destroyed. As it stands, though, we do have accounts of her behavior and of her speech at her trial on May 15, and they exhibit many of the same qualities as this letter. In both, Anne stands her ground bravely and articulately, but more striking, goes beyond the conventions of the time to venture into deeper political territory, exhibiting unusual insight into her own lack of humility and the possibility that this might have had something to do with her fall from grace.

When it was time for her to speak at her trial, after hearing the full charges for the first time—including trivial, non-criminal but “atmospherically” damaging accusations that she had made fun of the King’s poetry and taste in clothing—she made such “wise and discreet answers to all things laid against her” that “had the peers given in their verdict according to the expectations of the assembly, she had been acquitted.”[1] But of course, the verdict was not dependent on the impression Anne made, or how convincing her defense was. When she protested, against Smeaton’s confession, that “that one witness was not enough to convict a person of high treason”, she was simply informed, “that in her case it was sufficient.” Also “sufficient” were numerous bits of gossip that nowadays would be regarded as worse than hearsay, since they came from obviously prejudiced sources. George Wyatt, writing about the trial later, says that he heard nothing that could be considered evidence. Instead, as author Jane Dunn described the case, it was “a ragbag of gossip, innuendo, and misinterpreted courtliness.”

Anne almost certainly expected the guilty verdict that followed, which makes her calm, clear, and highly intelligent (according to numerous observers) responses to the charges all the more remarkable. It is less likely that she expected the sentence that followed: “that thou shalt be burnt here within the Tower of London on the Green, else to have thy head smitten off, as the King’s pleasure shall be further known of the same.” On hearing the verdict, several onlookers shrieked, took ill, and had to leave the hall. But Anne, as Chapuys observed, “preserved her composure, saying that she held herself ‘pour toute saluee de la mort’ [always ready to greet death], and that what she regretted most was that the above persons, who were innocent and loyal to the King, were to die for her. And then, as summarized by several onlookers, she delivered an extraordinary speech:

“My lords, I will not say your sentence is unjust, nor presume that my reasons can prevail against your convictions. I am willing to believe that you have sufficient reasons for what you have done; but then they must be other than those which have been produced in court, for I am clear of all the offences which you then laid to my charge. I have ever been a faithful wife to the King, though I do not say I have always shown him that humility which his goodness to me, and the honours to which he raised me, merited. I confess I have had jealous fancies and suspicions of him, which I had not discretion enough, and wisdom, to conceal at all times. But God knows, and is my witness, that I have not sinned against him in any other way. Think not I say this in the hope to prolong my life, for He who saveth from death hath taught me how to die, and He will strengthen my faith. Think not, however, that I am so bewildered in my mind as not to lay the honour of my chastity to heart now in mine extremity, when I have maintained it all my life long, much as ever queen did. I know these, my last words, will avail me nothing but for the justification of my chastity and honour. As for my brother and those others who are unjustly condemned, I would willingly suffer many deaths to deliver them, but since I see it so pleases the King, I shall willingly accompany them in death, with this assurance, that I shall lead an endless life with them in peace and joy, where I will pray to God for the King and for you, my lords.”

The clarity and confidence of Anne’s declaration here, her insight into her lack of humility, and her reference to “bewilderment” of mind are all, I believe, support for the authenticity of the May 6 letter. As to the letter’s bold attitude toward Henry, this was characteristic of Anne, and (as she acknowledged in her trial speech) she was aware that it overstepped the borders of what was acceptable. Her refusal to contain herself safely within those borders was what had drawn Henry to her; she could not simply turn the switch off when it began to get her in trouble. To do that would have been to relinquish the only thing left to her at this point: her selfhood. Ives says that it would “appear to be wholly improbable” for a Tudor prisoner to warn the king that he is in imminent danger from the judgment of God.” But Anne was no ordinary prisoner; she had shared Henry’s bed, advised and conspired with him in the divorce strategies, debated theology with him, given birth to his daughter, protested against his infidelities, dared to challenge Cromwell’s use of confiscated monastery money. Arguably, it was her failure to be “appropriate” that contributed to her downfall. Now, condemned to death by her own husband, to stop “being Anne” would have been to shatter the one constancy left in the terrible “strangeness” of her situation.

I don’t know for certain, of course, that this letter is authentic. But I have to wonder whether skeptics have been influenced by Anne’s reputation as woman known for her “feminine” vivacity, emotionality, and sexuality. 19th century editor Henry Ellis called this letter “one of the finest compositions in the English Language.”[27] Ellis lived at a time when women writers had come into their own. But perhaps not every historian has been as ready to acknowledge that someone like Anne could possibly have written “one of the finest compositions in the English language.”

[1] Cited by Alison Weir as Crispin de Milherve, but possibly Lancelot de Carles.

Purchase The Creation of Anne Boleyn: A New Look at England's Most Notorious Queen (US)

Purchase The Creation of Anne Boleyn: A New Look at England's Most Notorious Queen (US)

What a brilliant post! How this letter found among Cromwell’s things slipped by me during my research for SECRET DIARY I’ll never know. But to my ear it sounds like pure Anne. And it does have distinct similarities to the speech she gave at her trial. I’m with the 19th century biographers. Thank you for adding to my understanding of my favorite queen.

Hello Robin!!! It’s been way too long since we talked. My term ends soon. Shall we plan a phone call? And thank you for the lovely comment!

Would LOVE to catch up on the phone once your term ends. Just give me a shout when you’re free. I’m writing (a lot), but on no particular schedule.

Reblogged this on AntiWhiteQueen and commented:

As I now can return to “The Tudors,” I find Susan’s post about this possible letter of Anne’s very fitting. Enjoy!

This post popped up in my inbox right when I was reading Ives’s argument against the authenticity of the letter! It always hurts me to think she didn’t write it, because I so want her to have written it. I’m still not sure what my own opinion is, but I really enjoyed your argument for its authenticity! I guess we’ll never know for sure 😦

Reblogged this on Cari's Choices and commented:

An interesting train of thought.

Thanks Lisa! And never say never….Who knows what may turn up?

Brilliantly written argument and the letter does most certainly keep the timbre of Queen Anne’s final speech. My question would be what personal gain would someone have in forging the mentioned letter? It seems to me that anytime someone forges a document, they do it to benefit somehow. And; if it was forged why did Cromwell keep it?

Good questions, Mary! The discovery of the letter was first mentioned in bios written during and after the Elizabethan period (first by Lord Herbert in his 1649 “The Life and Raigne of King Henry the Eighth” and then by Bishop Burnet in 1679), when Anne, as the mother of Elizabeth, was being looked on more sympathetically by Protestants. Burnet says he found it, along with Sir William Kingston’s letters, “lying among Cromwell’s other papers.” But some thought it was planted there by an Elizabethan defender of Anne.

Thanks Susan, validating a person for religious conviction and justice could motivate a forgery. However, I am still leaning towards your reasoning that it is very possible that Queen Anne wrote the letter. I wish someone could pinpoint the date the parchment that it was scribed on.

If Anne didn’t write it, she SHOULD have. I lean toward believing it’s authentic and what we have is a copy made by Cromwell’s secretary.

Before the 1731 fire that burned some of the remaining records, John Strype claimed to have seen a second letter from Anne in which she furiously rejected a plea bargain which would require her to confess. (Probably wise of her, because I believe Henry would have killed her anyway, and would have been delighted to wave around “proof” of her crimes.) Perhaps the original of Anne’s “From the Lady in the Tower” letter was destroyed with it.

Pingback: An Argument for the Authenticity of Anne’s May 6th Letter to Henry | The son of Louis Chapuys and Guigonne Dupuys, was a Savoyard diplomat who served Charles V as Imperial ambassador to England

I never could fully agree that the letter was not authentic. Personally, I feel like the Anne Boleyn I’m familiar with would never go down without putting up a fight, which in this case, may or may not be this letter.