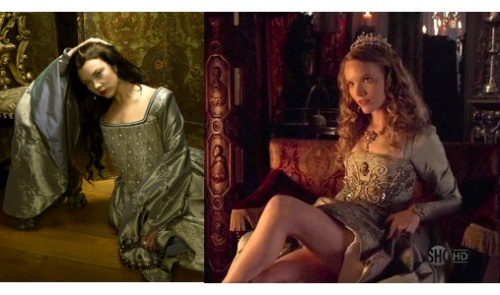

Above: The Tudors – glamorised, modernised and hyper-sexualised – depicts both Anne Boleyn (left) and Katherine Howard (right) as experienced seductresses.

Conor Byrne is a history student at the University of Exeter whose research interests include gender, cultural, and social history. His excellent blog focuses on historical issues but also touches upon contemporary political and social events.

None of the six wives of Henry VIII – with the possible exception of wife number four Anne of Cleves, who escaped her disastrous marriage with a lavish settlement and, more importantly, with her life – had enviable fates. But, Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard, wives number two and five respectively, came off worst by a long shot. Both were disgraced, shamed, and beheaded in the prime of youth. Anne was at most thirty-five (according to some writers, perhaps only in her late twenties), while Katherine probably never saw her eighteenth birthday.

It was Henry, an all-powerful, enigmatic and authoritative king, who was responsible for ordering the deaths of two women he had once passionately adored. It was Henry who personally signed Anne’s death warrant and, in the case of Katherine, consigned her to death using a Bill of Attainder – unlike her older cousin, she was never granted a public trial, an injustice that few people are aware about. It was Henry, therefore, both as a king and as a husband, who was responsible for the executions of two wives – even if he did not personally murder them.

Despite this, a prevailing view assumes that both women were, in varying degrees, to blame for their violent and untimely deaths. And, perhaps more shockingly, this is not a view that is limited to the popular imagination. Serious academic historians hold this view. Generally, historians believe that Anne Boleyn, although opining that she was a flirtatious woman who encouraged seductions in her chambers, was innocent of the crimes she died for, admitting that she was probably framed in what was a murderous and vicious court conspiracy, but they, by and large, contend that Katherine Howard was a silly flirt who actually did sleep around even after she’d married the king.

Take as an example the late Lacey Baldwin Smith, who wrote studies of both women. He appeared sympathetic to Anne Boleyn, admitting that she was ‘dispatched with callous disregard’, but his biography of Katherine Howard is littered with dismissive, contemptuous and curt phrases concerning the fifth queen. Katherine is frequently described by him as being ‘a common whore’, or a ‘juvenile delinquent’. Alison Weir, a bestselling popular historian, has argued in three books that Anne was innocent of sexual crimes and died as a result of Cromwell’s manoeuvres, but in her same works, Weir argues that Katherine was ‘certainly promiscuous’ and ‘incredibly stupid’. Suzannah Lipscomb has argued passionately for Anne Boleyn’s innocence, but is dismissive and patronising towards her younger cousin, depicting Katherine as ‘a stupid girl’ who, basically, deserved her fate. Even Joanna Denny, who wrote sympathetic biographies of both queens, alleged that Katherine committed sexual intercourse with Thomas Culpeper in a doomed attempt to pass off her lover’s bastard as the impotent king’s legitimate son. Only Retha M. Warnicke, a foremost Tudor scholar, has provided convincing arguments in favour of both women’s innocence, a view I subscribe to.

This article contends that Katherine is deserving of the same reassessment her more famous cousin has enjoyed over recent years. It is an interesting issue: why have scholars been ready to rehabilitate Anne Boleyn’s reputation and stress her innocence, but they have not rethought traditional – negative – assumptions about Katherine Howard? It is important to note here that some historians still perpetuate negative assessments of Anne. Alison Weir has defended the queen’s innocence and admires her courage, but she still paints a black picture of a manipulative, power-hungry shrew that was probably no virgin when she married the king. In popular culture, of course, The Other Boleyn Girl and company stress Anne’s supposed seductive and promiscuous nature. But, by and large, it’d be fair to say that the majority of modern historians have rethought traditional scholarship surrounding her.

Perhaps, however, the fundamental reason why Katherine has not received the same reassessment is because she admitted to flouting the gender rules of the time, as Warnicke suggests, pointing out that Katherine admitted to meeting with Culpeper after she married the king – a dangerous and suspicious activity for any married woman in the early modern period, especially a royal wife. Anne, of course, did not admit to any such activity, and only one of the five men accused with her did, perhaps because he was tortured. Another reason might be because Anne’s innocence has been, for most people (with the exception of some historians such as G. W. Bernard) patently obvious, in no small part, I feel, because of the incredible impact she made at her trial just four days before her execution. For many people, the powerful, evocative and most importantly, convincing, defence offered by Queen Anne at her trial in May 1536 has stood the test of time, and has effectively proven to most people that she was innocent. Contemporary observers themselves were swayed by the power behind her words and the conviction in her voice. They changed their opinions and voiced their suspicions that she was being done away with for ignominious reasons that the official charges were only a cover for. But Katherine was never granted this opportunity. Holed away in Syon Abbey, with rumours that she was contemplating suicide and suffering a mental breakdown, she left it only to make the short journey to the Tower, where she was quickly dispatched days later.

Consider the images presented here of Natalie Dormer as Anne Boleyn and Tamzin Merchant as Katherine Howard from the TV series The Tudors. Both women are presented as scheming and experienced seductresses who flirtatiously ensnare the king, although, of course, Anne’s character becomes much more complex, multifaceted and admirable over the course of the series as we are exposed to her religious role, political involvement, and humanist interests (in no small part because of Natalie Dormer’s conviction that Anne needed to be portrayed in a more two-dimensional light). Merchant’s Katherine, however, is dim, spoiled and unpopular, although her beauty captivates both the king and Culpeper. This depiction of these women as promiscuous, however, is not limited to The Tudors: consider, for example, a scheming and jealous Anne Boleyn in The Other Boleyn Girl who openly seduces the king in a barely believable scene before the whole of his court or a naked and sensual Katherine Howard in the BBC TV series Henry VIII (2003) who receives Thomas Culpeper while bathing.

But the paradox is: while popular culture often depicts Anne as a scheming seducer, by and large the general public are now coming around to the view that, in reality, it was a lot more complicated, in no small part to the efforts of both academic and popular historians. So even though Anne may still be presented as promiscuous in pop cultural texts, the majority of informed viewers know that the real woman was very different. But it is not the same with Katherine Howard: because so few historians have sought to rehabilitate her reputation, the prevailing image of her in popular culture, by and large, reflects the opinions of many serious historians, and is not consciously challenged by viewers in the same way that, for example, a negative depiction of Anne would be.

I conclude this article, therefore, with a plea for Katherine to be reassessed. We have now recognised, over the course of time, that Anne Boleyn was a complex, talented, multifaceted individual and we are able to dismiss the traditional caricature of her as whore, witch or home wrecker. I hope that, one day, the same will be achieved for her tragic and younger cousin.

Purchase The Creation of Anne Boleyn: A New Look at England's Most Notorious Queen (US)

Purchase The Creation of Anne Boleyn: A New Look at England's Most Notorious Queen (US)

Interesting article. IIRC, Victorian-era writer, Agnes Strickland thinks that Katherine Howard might well have been innocent, also;. David Starkey’s thoughts about Katherine Howard are (IMO) somewhat unusual — he stresses her kindliness in seeking pardons for others, and, in trying to make Margaret Pole more comfortable while she was imprisoned. This might trigger the re-assessment.

I’m beginning to think Katherine is innocent as well. Only for this reason: if your husband’s last wife was beheaded for adultery, would you be stupid enough to commit the same crime yourself?

Not sure I agree here, the reason for getting rid of Anne was the same as Catherine of aragon….still no male heir, it seems Henry was infatuated with Katherine Howard right up until he found out she had committed adultery, he had a male heir at the time so there was no great urgency to get another wife, I think she was probably guilty, she did admit it also which Anne never did

Lisa, that is exactly my point. I don’t believe Katherine was stupid and I’m convinced she wouldn’t have voluntarily chosen to meet with Culpeper, given that she surely knew that her cousin had died for less. I’m certain that the Howards would have drummed into their family members the horrific fate suffered by a Queen in 1536, whose mother was after all a Howard. If Katherine was coached by her family when the king began courting her, as is likely, it seems certain they’d have warned her of Anne’s horrific end and basically emphasised the need not to follow her example.

Esther, I praise Starkey for his reinterpretation of Katherine, especially his claim that she didn’t sleep with Culpeper. But aside from that, I find his view seriously problematic. He takes the interrogations at face value and so believes it when Culpeper claimed the Queen was dying of love for him. Starkey fails to appreciate that this was a standard interpretation of early modern women, and doesn’t appreciate that Culpeper was trying to transfer guilt to Katherine. So I disagree with his view. Basically, Warnicke’s interpretation of Katherine being a victim of sexual abusers seems to me the correct one.

Let’s not forget that Katherine admitted that Dereham had raped her, and Culpeper was rumoured to have raped a park keeper’s wife. Seems she, unfortunately, attracted violent men.

Lisa, I don’t believe Katherine was stupid (probably the most irritating myth about her in existence), and so that raises a big issue: I don’t believe she would have been stupid enough to commit it. None of the evidence seems to indicate she met with Culpeper voluntarily. Only details of her fear and anxiety emerge. I think the death of Anne Boleyn would have been a huge shock to the Howards, especially since her mother was a Howard, and I would guess that it would have been drummed into Howard family members of the need to be chaste, pure, etc. to avoid an awful fate that had befallen one of its own members. Even if Katherine was not informed of this during her childhood (and she probably was), her family would have emphasised this to her when she was being courted by the king, when as most historians suggest, they probably coached her. Furthermore it was against the rules for early modern women to meet secretly with men who were not their husbands. If this custom is taken account of, then it becomes so difficult to understand why Katherine would have met with Culpeper, unless she was in love with him and deliberately flouted the rules, which I find unconvincing on so many levels, or because he was blackmailing her through Lady Rochford, which Warnicke argues.

Esther, I agree that David Starkey’s reinterpretation was positive in identifying Katherine’s achievements as queen (often ignored by historians) and in arguing that she never slept with Culpeper. Aside from that, I find his theory that she and Culpeper were in love with one another seriously problematic. By taking at face value the interrogations, Starkey seems to ignore the fact that Culpeper was displaying typical behaviour for an early modern man in identifying the woman as to blame for such matters. Why did he continue stressing that the Queen was dying of love for him and pressurising him to meet with her? Not because, as Starkey indicates, she was in love with him, but more likely because he was trying to deflect blame away from itself by displacing it onto her. Such a reading seems to me obvious, given what we know of early modern attitudes to sexuality. These interrogations have to be scrutinised and read in line with cultural expectations and attitudes.

The issue that Anne did have a “trial” and a public hearing is something I had overlooked. The record (or reports of her defense) make all the difference to modern historians, one suspects. Now, I must re-read my copy of Denny – I seem to recall it as somewhat sympathetic, but equally patronising. So easy to be patronising of a teenage woman! Jane Parker, Lady Rochford, is an extraordinary figure in the tragedies of the two queens. Did she simply develop an unbalanced hatred of the Boleyn/Howard clan?

But I’m not sure it’s right finding Catherine innocent at the expense of the men’s reputations. There is no evidence that she was a victim of sexual abuse and although Culpeper appears to have been an unsavoury character, in that he or his brother were involved in a rape and murder, we don’t know for sure what he was like and he appears to have been in love with Catherine. Those two men were also victims of Henry VIII and I’d hate to seem them tarnished and used as scapegoats.

Hi Claire, thanks for your comment.

I think it may have been unwise for me to have referred to the rape rumour surrounding Culpeper, as in my book, I actually dismiss it. I think it’s probably false. I don’t think that a monarch as obsessed with honour as Henry VIII was would have favoured a man who was associated with rape and even murder. So I dismiss that one.

I have to disagree however regarding the suggestion that Katherine was not a victim of sexual abuse. My theories draw on Retha Warnicke’s, advanced in her book “Wicked Women of Tudor England”. As she states, and I agree with her, a clear pattern emerges with Katherine: abused by Manox at twelve (and I believe of the men she was involved with, Manox clearly WAS an abuser), seduced by Dereham at fourteen, and manipulated by Culpeper during her marriage. I also have to disagree regarding suggestions that Culpeper was in love with Katherine, as I suggested regarding David Starkey’s theories, again building on Warnicke’s interpretation. I just do not think the historical record supports the view that he did. Why, especially, would Katherine, who was aware of early modern codes that dictated that women do not spend time alone with men who were not their husbands, and whose cousin had been beheaded for alleged flirtations, have risked her life to meet him?

The greatest piece of evidence to me to support the view of Culpeper blackmailing the queen is the fact that he began entreating her to meet with him in the spring of 1541, when two important events occurred: firstly, Dereham arrived at court and began boasting of his affairs with the queen (Culpeper almost certainly found out). Secondly, and more seriously, the king fell seriously ill, and there were even rumours of his impending death. I think these factors created a series of circumstances that led to the meetings between queen and courtier. Culpeper may have believed that, if the king died, a vulnerable and young queen would be open to political manipulation and pressure.

I have so many questions and problems with the traditional view: If they were so in love with one another, why did they not begin meeting in 1540, when Katherine had just married the king? If they were committing adultery, why did no ladies speak out against it until, conveniently, the autumn of 1541, when they were pressured to do so by government officials? If the queen’s behaviour was so suspicious, why was no mention raised during the court progress? Why did Katherine insist Lady Rochford remain nearby when she met with Culpeper, and reprimanded her when she began moving away? Why did she tell Culpeper she did not want to meet with him anymore? Why does her supposed letter to him refer to death and suffering, at a time when her state of mind was ‘jittery’, if she was in love with him?

The answer, to me, is obvious. She was not meeting with him voluntarily. I am not intending to prove her innocent to the detriment of other men. That is not and never has been my intention. I think she was reckless enough in meeting with him, when it was frowned on at the time to do so. But all of the questions raised above, coupled with her history, suggest to me that she was coerced, as a vulnerable and inexperienced queen. Certainly I think Dereham was aggressive and controlling – surely his behaviour at court proves that; he not only spoke treasonously, but he was pressurising the queen. Manox seduced her in dark places and Culpeper blamed her for their meetings. Surely, if Culpeper loved her, he would not have done so. I have researched in depth these sources and I have read a lot about early modern sexuality. The men were victims of Henry VIII, but they in turn victimised a queen, especially Dereham through his controlling behaviour both before and at court. To me, my interpretation is extremely plausible.

Pingback: “There Was Never Such a Whore”: The Downfalls of Queens Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard | The son of Louis Chapuys and Guigonne Dupuys, was a Savoyard diplomat who served Charles V as Imperial ambassador to England

Cbyrnex wrote: “I don’t believe that …”, “I’m convinced that…”, “I’m certain that…”, “It seems certain that…”, “I disagree with his view”, “[the other view] seems to me the correct one”.

What do personal convictions such as the above have to do with a scholarly debate? All hypotheses should be on the table, none of them barred because they are a priori rejected because of ‘beliefs’.