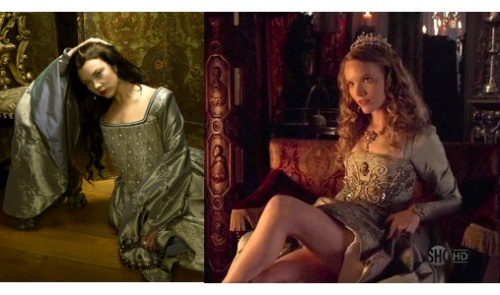

During the episode of The Tudors in which Anne Boleyn is executed, scenes of her suffering in the Tower are punctuated with the image of Henry, gazing contemplatively at two beautiful swans nuzzling in the pond outside the palace. His mood and thoughts are left deliberately ambiguous; perhaps, the viewer imagines, he is thinking back over his love for Anne and the life they shared together, perhaps he is having regrets, feeling sorrow for the beauty that is about to be lost? No. After the execution scene, we are immediately taken to the King at his table, looking forward to his breakfast, which is being brought to him in a large gilt tureen on a silver platter. The lid is lifted, and the servants and nobles surrounding Henry gasp and applaud in delight. There on the platter is one of the swans, roasted and decorated with its own beautiful wings, posed as gracefully as if it were still swimming in a lake. Henry, referencing Charles Laughton’s famous eating scene but giving Henry’s voraciousness a menace missing from Laughton’s comic depiction, tears off a wing, plunges his hand into the body of the swan, and begins eating, oblivious to the greasy drool spilling from his mouth.

During the episode of The Tudors in which Anne Boleyn is executed, scenes of her suffering in the Tower are punctuated with the image of Henry, gazing contemplatively at two beautiful swans nuzzling in the pond outside the palace. His mood and thoughts are left deliberately ambiguous; perhaps, the viewer imagines, he is thinking back over his love for Anne and the life they shared together, perhaps he is having regrets, feeling sorrow for the beauty that is about to be lost? No. After the execution scene, we are immediately taken to the King at his table, looking forward to his breakfast, which is being brought to him in a large gilt tureen on a silver platter. The lid is lifted, and the servants and nobles surrounding Henry gasp and applaud in delight. There on the platter is one of the swans, roasted and decorated with its own beautiful wings, posed as gracefully as if it were still swimming in a lake. Henry, referencing Charles Laughton’s famous eating scene but giving Henry’s voraciousness a menace missing from Laughton’s comic depiction, tears off a wing, plunges his hand into the body of the swan, and begins eating, oblivious to the greasy drool spilling from his mouth.

Had Henry become the monster depicted in this scene?

The execution of a queen was unprecedented, extreme and shocking, even to Anne’s enemies. Henry had invested six years of time, energy, intellect, money, and blood in making the marriage happen. They were married less than three years. There is no evidence of an unbridgeable emotional estrangement between them. His earlier love letters to her, admittedly written in the bloom of fresh passion, portray a solicitous, tender suitor whom it is impossible to imagine coldly ordering a wife’s death. There are plenty of explanations for Henry’s desire for a new marriage–Anne’s failure to provide a male heir, Jane Seymour, waiting in the wings, fresh and fertile, Henry’s recognition that Anne was creating problems with his image. In the end, however, it still takes a leap of incomprehension to find any of them sufficient to explain Henry’s willingness—in fact, seeming eagerness—to sign the order for Anne’s execution. We are still left asking ourselves: How could he do it? What follows are six different “answers,” not all of them incompatible with each other, but all offering a slightly (and in one case radically) different “take” on one of the most notorious death decrees in history:

- Suzannah Lipscomb: After a year of physical and emotional disasters, the wound to Henry’s masculine honor and the need to restore patriarchal authority was all-important:

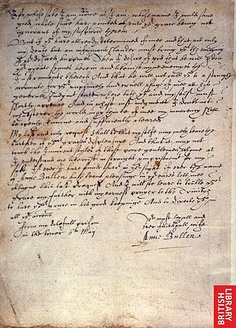

“Two contemporary comments provide a clue [to Henry’s behavior]. Cranmer, in his letter to the king concerning his disbelief at Anne’s guilt, wrote that he could not ‘deny but your grace hath great causes…of lamentable heaviness; and also, that…your grace’s honour of every part is so highly touched’, before rushing on to undo these words by disingenuously assuring Henry, ‘if the reports of the Queen be true, they are only to her dishonor, not yours’. A similar sentiment was expressed by a European observer, the reformer Philipp Melancthon, when he wrote, ‘see how dreadfully this calamity will dishonor the King’. Honour, as we have seen, was chiefly a measure of one’s ability to conform to the ideals demanded of one’s gender. For a man, it meant exerting masculinity, imposing patriarchy, controlling the women in one’s household, maintaining a good reputation and demonstrating physical and sexual prowess. Chiefly, it meant controlling the morality of the women under his care and, specifically, their sexual morality. That henry had been unable to do this denoted two things: it was evidence of Henry’s inability as a man and as a monarch. Contemporary thought made a clear link between a man’s sexual potency and his wife’s fidelity – men who were cuckolded were those whose ‘lack of sexual dominance led their wives to adultery’. ‘To be a man’, writes Lyndal Roper, ‘was to have the power to take a woman.’ Anne’s very behavior, if assumed to be true, testified to the king’s lack of manliness, and as if this weren’t enough, Anne and Rochford’s ridicule of the king on this very matter drove the point home. It was not something that went unnoticed in the kingdom. Sir Nicholas Porter, the parson of Freshwater, was reported to have said in 1538, ‘Lo, while the King and his Council were busy to put down abbeys and pull away the right of Holy Church, he was made cuckold at home.’ There was also a strong connection in the popular mind betw4en impotency and old age – the image of ‘Old Adam’ whose feeble old body could not satisfy his vigorous young wife was a constant refrain in the ballads found in contemporary broadsides. There were huge repercussions if such a failure were found in a king. Early modern thinking linked the governance of a house with the governance of a realm; as John Dod and Robert Cleaver wrote in 1612, ‘it is impossible for a man to understand how to govern the commonwealth, that doth not know how to rule his own house’. Any woman’s adultery, but especially that of a queen, upset the social order and gender hierarchy upon which society was based. Cranmer was right the first time – Henry’s honour was ‘highly touched’ by Anne’s apparent adultery. This also explains why Henry felt the need to cavort himself with ladies and increase the pace of his relationship with Jane Seymour, marrying her so quickly. It wasn’t just, as Alesius later hypothesized, that he was ‘openly insulting’ Anne: in the light of Anne’s devastating assault on his masculinity, Henry did it to restore the patriarchal order and to prove his manhood.”

(From 1536: The Year that Changed Henry VIII, p. 88-89)

- Alison Weir: Henry VIII, ready to believe anything about a woman he had come to see as a monster, found the charges against Anne entirely credible:

“From the time of Anne’s committal to the Tower, Henry VIII’s behavior was typical of a man confronted with appalling evidence of his wife’s infidelity, and whose masculine pride has been deeply wounded. He avoided parading his humiliation in public, and remained incommunicado until all was over. Henry was apparently ready to believe anything of Anne. He would shortly manifest the conviction that she was a monster not only of lechery but also of cruelty. The latter was, to him, probably entirely credible. She had hounded Wolsey night until death; repeatedly urged henry to send Katherine of Aragon and Mary, his own daughter, to the scaffold; been ruthless against her enemies. Five years earlier, rumor had placed her faction behind an attempt to poison John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, and out-spoken and upright opponent of the Boleyns; and only a couple of months ago it was bruited that Katherine of Aragon had been poisoned, and that Anne was the culprit. Now it appeared she had plotted to do away with the King himself, her own husband. That certainly gave Henry a jolt, and his imagination began to run riot. When his bastard son, the seventeen-year-old Henry FitzRoy, Duke of Richmond, came on the evening of May 2 to receive his father’s blessing before retiring for the night, “the King began to weep, saying that he and his sister {Lady Mary} were greatly bound to God for having escaped the hands of that accursed whore, who had determined to poison them. These tears were the only ones Henry is known to have shed in connection with Anne Boleyn’s fall, while his tirade betrayed his conviction that she was guilty of far worse than adultery, and the sharp-minded Chapuys picked upon this: “From these words, it would appear the King knows something about it.”

(From The Lady in the Tower, pgs. 150-151)

- G. W. Bernard: Lancelot de Carles’ poetic account of remarks by the Duchess of Worcester, combined with Anne’s outrageously flirtatious behavior, strongly suggest that Anne was indeed guilty of at least one adultery:

“Also just possible, of course, is that everything we have considered was no more than a series of misunderstandings in response to ‘unguarded speech and gossip’, ‘a lot of smoke but precious little fire’. After Anne, in the Tower, told Kingston about Mark Smeaton, her mother rebuked her: ‘such desire as you have had to such tales has brought you to this’. It is just about possible that the countess of Worcester had herself read too much into what she thought she had seen, not just in the case of Anne’s brother, but of all she spoke of. It is also just about possible that Anne’s burblings in the Tower could be innocently explained away – but, crucially, that what henry learned was amply sufficient to make him, reluctantly but reasonably, conclude that, alas, it was all true and then seek furiously to deal with those who had wronged him. Was it that, although there was no evidence that Anne was guilty, enough had been said to make Henry understandably and sincerely believe that she was? Yet the countess of Worcester was in absolutely no doubt about Anne’s behavior – and she was in a very good position to know the truth. If what she said was wholly wrong, we should have to believe either that she deliberately invented the charges she brought against Anne or that she utterly mistook what Anne was, and was not, doing in her chamber. It is far more plausible that the countess was not totally wrong and that if, perhaps, she read too much into George Boleyn’s visits to his sister’s chamber, there was still a good deal of truth in what she declared about Anne’s behaviour. And so it remains my own hunch that Anne had indeed committed adultery with Norris, probably with Smeaton, possibly with Weston, and was then the victim of the most appalling bad luck when the countess of Worcester, one of her trusted ladies, contrived in a moment of irritation with her brother to trigger the devastating chain of events that led inexorably to Anne’s downfall.”

(From Anne Boleyn: Fatal Attractions, pgs. 191-192)

4. Michael Hirst (creator of The Tudors): Anne’s failure to produce an heir was not just a blow to the security of the Tudor line but a sign that the hope that Henry had built his entire life around was based on an illusion- that he had spent years of his life, shed the blood of friends, and broken with the church of his childhood, only to be proved mistaken in the supposition that this was what God wanted of him:

“He had attacked the church on the basis of a love affair, largely. But he felt sure of what he was doing at the time, and Anne had mistaken promised him a son. After she’d given him a daughter and had the miscarriages, it began to seem to him as though he’d gone horribly wrong. He was plunged back into reality, which is messy and not perfect. And I think that as he confronted the huge seriousness of it, he began to think in weird ways, that she was a witch and so forth. This of course, shows how juvenile he still was. And he did have an absolutely ruthless streak which his father, too, had possessed. But beyond that, he did suffer a severe psychological crisis, knowing he had been so deluded. He came out of that crisis a much worse person, a complete tyrant and monster, who killed off the best part of himself in the attempt to reconcile his psychological issues.”

(From a personal interview with Susan Bordo)

- Kyra Kramer: Henry was suffering from a genetic disorder that radically altered his mental state as he grew older, resulting in more and more erratic and irrational behavior.

“Who in their right mind would stalk a woman until she gave in and dated him, wait several years to marry her and be allowed to consummate the relationship, rip a country apart and declare his own daughter a bastard in order to keep his new bride, and then kill that same beloved woman just a few years after saying “I do”? No one, that’s who.

Well, no one in his or her right mind that is.

According to a theory put forth by Dr. Catrina Banks Whitley and myself, Henry VIII was not actually in his right mind when he had Anne Boleyn legally murdered. The theory postulates that Henry had a Kell positive blood type concurrent with McLeod syndrome, resulting in reproductive losses and an altered mental state in his forties.

McLeod syndrome can only be manifested in people, who are thus far always men, with a Kell positive blood type. (Before the medical specialists comment – yes, one can have K(K1) effecting pregnancies and the father still express McLeod syndrome because of variant Kell antigen expression: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6879675 ) Usually the symptoms of McLeod syndrome begin to appear near the patient’s fortieth birthday and grow progressively worse over time. Those symptoms can include physical issues, such as muscle and nerve deterioration, facial tics, malformed blood cells, and damage of the internal organs like the liver and the heart. The disease is also often expressed by an erosion of mental stability, wherein the patient becomes more and more irrational and erratic.

There is a plethora of evidence to show how Henry’s personality and mental processes changed in the 1530s, which I have room to explicate more fully in my book, Blood Will Tell, but you’ll have to trust me on for now. The kinds of psychopathology exhibited by patients with McLeod syndrome include, but are not limited to, deterioration of memory and executive functions, paranoia, depression, socially inappropriate conduct, and can even get so bad that it mimics schizophrenia-like behaviors. In severe cases, “schizophrenia-like symptoms” of personality changes can be the “prominent initial clinical manifestation” of McLeod syndrome. This abrupt mental change would explain why Henry started his reign as a puissant prince but ended it as a pestilent putz.

Moreover, the timing fits McLeod syndrome like a glove. Henry turned forty in the summer of 1531, and shortly thereafter his treatment of Queen Katherina turned much harsher. For the first couple of years she was the only victim. By the time he was forty-four the King’s personality alterations were becoming clearer in the most disturbing ways. In spite of his enduring reputation for tyranny, he only started wantonly killing people who disagreed with him in 1535, the year he beheaded Thomas More. Before that, getting him to agree to an execution was like pulling teeth. Cardinal Wolsey had a devil of a time getting him to execute even the Duke of Buckingham, who was blatantly gunning for Henry’s throne.

(While most people remember 1536 as the watershed year for Henry’s new fondness for the axe, because that is the year he beheaded Anne Boleyn, he actually started his killing spree in 1535. Incidentally, the bloodbath began several months before he fell and was knocked unconscious during a tournament in January of 1536. That means that the blow to the head may have exacerbated his symptoms, but the alteration in his personality had already started more than a year before. )

Henry’s relationship with Anne Boleyn neatly straddles the manifestation of his mental symptoms. The King started pursuing Anne in 1525 (maybe as early as 1524) and beheaded her in 1536. Prior to his fortieth birthday he is clearly her besotted swain, yet he was still trying to please everyone and let Katherina down gently (good luck with that, bub). After his fortieth birthday he becomes increasingly cruel to Katherina, and then murderous to anyone who disagrees with him, and then turns abruptly and viciously on the woman he had loved so dearly.

Personally, I happen to agree with Walker, and think Anne’s death was not caused by her miscarriage in January of 1536, but rather because she told a courtier that he wished for “dead men’s shoes” in April. That statement could be constructed as imagining the death of the King, which was treason. Her enemies, under Cromwell’s management, pounced on her slip of the tongue and convinced Henry she was plotting his death. A little torture of Mark Smeaton and his confession of adultery — voila, she is a whore and Cromwell can conveniently rid himself of some of her supporters.

Henry, having become paranoid and irrational due to McLeod syndrome, was easy prey to manipulation by Anne’s foes. Once he had signed off on his wife’s beheading, his imagination ran wild. Soon the King had convinced himself that Anne had been plotting to poison his older children and that she had slept with more than one hundred men. Rational people do not suspect a woman under the constant lack of privacy Anne faced to have had sex with one hundred men.

The man who killed Anne Boleyn was clearly not the same kind and gentle knight of his youth, and he would grow steadily worse after her death. Nowadays, most people only remember the villainous brutality of the last fifteen years of his reign, and have very little idea of the gentle and intelligent man the King was until the 1530’s. I really hope that one day his remains can be exhumed for DNA analysis. If he did have McLeod syndrome, perhaps people will forgive him for the crimes he committed as a result of an uncontrollable mental illness. If nothing else, I hope the evidence I present in my book will at least encourage people to see Henry VIII as the complex monarch he was, rather than an unmitigated monster.”

(Based on the arguments of Blood Will Tell.)

6. Susan Bordo: Henry’s resilience, emotional balance, and temper may indeed have degenerated as he got older, possibly exacerbated by genetic factors as well as the challenging events of 1536, but he was always a dangerously capricious personality:

“Henry was always a man of many faces, a “baffling composite of shifting silhouettes” (Lacey Baldwin Smith) who could be good-natured, generous and charming one moment and dangerously cold as stone the next, highly emotional yet rigidly stubborn, a genuine searcher of his conscience for “God’s will” yet able to subordinate all moral scruples and guilt to solidifying his own authority or satisfying his own desires. The combination of informal warmth and lethal self-interest meant that even the closest relationships with him were never on solid ground, always skating on thin ice. Thomas More, of all of Henry’s contemporaries, was most perceptive about the inherent danger of making too much of the King’s outward gestures of affection. He told Fisher that “the king has a way of making every man feel that he is enjoying his special favor.” It may have been a compliment, but it was also a warning. He told a young courtier—and this was in 1520, before any “crisis” had occurred in Henry’s reign—that having fun with the king was like “having fun with tamed lions—often it is harmless, but just as often there is the fear of harm. Often he roars in rage for no known reason, and suddenly the roar becomes fatal. The pleasure you get is not safe enough to relieve you of anxiety. For you it is a great pleasure. As for me, let my pleasure be less great—and safe” (Lion’s Court, p. 217).

But even More couldn’t remain safe. He realized, as he told his son in law Roper, that even when he was favored by the King “more singularly” than any subject in the realm, “I have no cause to be proud thereof, for if my head could win him a castle in France, it should not fail to go.” (Ridley, 188) In the end, Henry was just that cavalier with More’s life, although not over a castle in France. Henry had promised, years before, that he would always allow More to avoid any declarations or actions that went against his conscience. But when Henry’s own supremacy was at issue, More’s conscience—and his head—proved to be easily dispensed with. On the day of More’s execution, Henry went hunting in Reading. This was the way Henry dealt with all his executions of old friends and lovers: go hunting, have a party, be merry. Move on. He was shockingly capable of decisively and irrevocably turning off the switch of affection, love, tender feeling and shared memories, severing all ties, and refusing to look back.

In fact, those whom he loved the most—Wolsey, More, Anne, Cromwell–were most at risk. Because he loved them, they had the most power to disappoint him—and for Henry, disappointment could never be “slight.” All wounds to his authority, his manhood, his trust, were bloody gashes that he could only repair by annihilating (psychologically or literally) the one who inflicted the wound. This, perhaps, is what distinguishes Henry’s pattern from “ordinary” royal imperiousness. Kings execute people. Kings have grandiose ambitions. Kings are threatened by challenges to their authority. Kings can become drunk on power, and often do. But Henry may be unique among famous authoritarian kings in that his close relationships only had two switches: on and off. As Howard Brenton, author of the play Anne Boleyn, put it in an interview with me, “With Henry, you were either totally in or you were dead. He would have someone close to him, he’d elevate them, and they’d be terrific and virtually run everything on his behalf, and then when something went wrong, or a wind came his way, he would turn 180 degrees against them and they would be out. It happened to Wolsey, it happened to More, it happened to Anne, it happened to Cromwell.” It almost happened to Mary, who so enraged Henry when she refused, even after Anne was dead, to take the oath recognizing her father as Supreme Head of the Church of England, that Cranmer , at the last minute, had to talk him out of ordering her execution (Ridley, 274). Mary was Henry’s daughter.

And his will was capricious. The letters of ambassadors, even from the early years of his reign, describe sudden, explosive angers, “tears and tantrums.” In 1535, the king’s fool almost lost his life over a joke about Anne Boleyn; a year later, Henry was weeping uncontrollably while hugging his illegitimate son, relieved that he was now safe from “that accursed whore” who had slept with over a hundred men. A hundred? That would have meant a new man every ten days of her Queenship. Yet it’s possible that Henry believed something near to this, for his emotional switch, for whatever reasons, had turned against her, and she was now as wholly evil in his eyes as she once was wholly virtuous.

Whatever the origins of Henry’s personality, his problems were vastly exacerbated by the fact that he was, after all, king. As such, he was continually flattered and pampered, his every whim indulged, his grandiosity rarely challenged, his illusions carefully maintained. All of this encouraged his sense of omnipotence, which in turn made it all the riskier for those around him to show anything less than absolute allegiance. In proving this, even obedience, ironically, put one at risk, for Henry wasn’t a fool; he knew those around him were afraid, and so never fully trusted anyone. When he was young, he sought out people like More, and encouraged them to be honest with him, seeking some solid ground on which to base a relationship. But it was a zero sum game; when More ran up against Henry’s need to be the center of the universe, More’s once-cherished independence of mind became worse than “nothing” in Henry’s “all or nothing” demands on relationships.

It’s hard to know exactly what threw the switch with Anne. Her final miscarriage may have convinced him that God was not on the side of their relationship. He may have believed in the charges of adultery—although his exaggerated estimates of her infidelities make me less rather than more likely to believe that; if he truly believed she had slept with five men, including her own brother, surely that would have been enough to “justify” his outrage without dragging half the men in court into her bed. Or the humiliation of hearing that Anne gossiped about his lack of sexual performance may have been all that was needed. We will never know, and it really doesn’t matter. It was sufficient, whatever it was, to shut off any currents of empathy, memory, attachment that Henry felt for Anne. This is where “Anne of the Thousand Days” has it so wrong. The play and movie both open with Henry tormented by the decision whether or not to order Anne’s execution. In Maxwell Anderson’s play, which is written in verse, Henry muses:

“This is hard to do

when you come to put pen to paper.

You say to yourself:

She must die. And she must—

If thing are to go as planned.

Yes, if they are to go at all.

If I am to rule

And keep my sanity and hold my England off the rocks…

Go back to it, Henry, go back to it.

Keep your mind

On this parchment you must sign.

Dip the pen in the ink write your name…

It’s only that a woman you’ve held in your arms

And longer for when she was away,

And suffered with her—no, but she promised you an heir.

Write it down—

Write Henry Rex, and it’s done.

And then the headsman

Will cry out suddenly, “Look, look there!’

And point to the first flash of sunrise,

And she’ll look,

Not knowing what he means, and his sword will flash

In the flick of sun, through the little bones of her neck

As she looks away,

And it will be done.

It will be done.”

It’s romantic and moving, and beautifully written. But it is not, I believe, the poetry of Henry’s reality. In that reality, they handed him the parchment. He dipped the pen in the ink. He signed his name: Henry Rex. And it was done.

Based on material from The Creation of Anne Boleyn: A New Look of England’s Most Notorious Queen, available in a US edition or a UK edition.

Anne too wished to have the thing done. Yet, cruelly, the execution was delayed twice, once in order to clear the Tower of possible sympathetic observers, the second time because the executioner had been delayed. The first delay dismayed Anne, who thought that at the newly appointed hour she would already “be dead and past my pain.” Kingston, who seems to have been an absurdly literal man, took her to be referring to the physical pain of the execution itself, and reassured her that “there would be no pain, it was so subtle.” Anne replied with her most famous line: “I have heard say the executioner is very good, and I have a little neck.” And then, according to Kingston, “she put her hand around [her neck], laughing heartily.” Kingston flat-footedly interpreted this to mean that Anne had “much joy and pleasure in death.” He apparently did not “get” Anne’s irony. At the news of the second delay, she was distraught. But “It was not that she desired death,” as she told Kingston (or perhaps one of the ladies, who then told him) “but she had thought herself prepared to die, and feared that the delay would weaken her resolve. “ So much for Kingston’s theory that Anne felt “joy and pleasure” at the prospect of death.

Anne too wished to have the thing done. Yet, cruelly, the execution was delayed twice, once in order to clear the Tower of possible sympathetic observers, the second time because the executioner had been delayed. The first delay dismayed Anne, who thought that at the newly appointed hour she would already “be dead and past my pain.” Kingston, who seems to have been an absurdly literal man, took her to be referring to the physical pain of the execution itself, and reassured her that “there would be no pain, it was so subtle.” Anne replied with her most famous line: “I have heard say the executioner is very good, and I have a little neck.” And then, according to Kingston, “she put her hand around [her neck], laughing heartily.” Kingston flat-footedly interpreted this to mean that Anne had “much joy and pleasure in death.” He apparently did not “get” Anne’s irony. At the news of the second delay, she was distraught. But “It was not that she desired death,” as she told Kingston (or perhaps one of the ladies, who then told him) “but she had thought herself prepared to die, and feared that the delay would weaken her resolve. “ So much for Kingston’s theory that Anne felt “joy and pleasure” at the prospect of death. What she may have felt was something closer to what James Hillman describes as the state of mind that often precedes an attempt at suicide: a desperate desire to shed an old self whose suffering had become unbearable, and thus be “reborn” in the act of dying. This imagined rebirth, for Hillman, has nothing to do with belief in reincarnation, or even in heaven, but the perception, ironically, that the soul cannot survive under existing conditions. What Anne had been through was certainly enough to shatter any hold her previous life may have exerted on her. She had been discarded by the man who had pursued her for six years, fathered her daughter, and seemingly adored her for much of their time together. The person she was closest to in the world—her brother George—had been executed on the most hideous and shameful of charges. The rest of her family, as far as we can tell, had either abandoned her or—as Anne believed of her mother–was awash with despair and grief over what was happening. Still recovering from a miscarriage, her body and mind undoubtedly assaulted by hormonal changes and unstable moods, she had been sent to prison on absurd, concocted charges, and “cared for” there by women who were hostile spies. She knew she would never see her daughter Elizabeth again, and—unlike the fictional Anne of Anne of the Thousand Days, who predicts that “Elizabeth will be queen!”—had no hope, after Cranmer’s visit, that her child would ever be anything more than she had seen Mary reduced to: a bastardized ex-princess forced to bow down to any children the new wife might produce for Henry. She had been given reason to hope that she would be allowed to live, only to have those hopes crushed at her sentencing. In a sense, she had already been through dozens of dyings. Nothing was left but the withered skin of her old life, which she was ready to shed.

What she may have felt was something closer to what James Hillman describes as the state of mind that often precedes an attempt at suicide: a desperate desire to shed an old self whose suffering had become unbearable, and thus be “reborn” in the act of dying. This imagined rebirth, for Hillman, has nothing to do with belief in reincarnation, or even in heaven, but the perception, ironically, that the soul cannot survive under existing conditions. What Anne had been through was certainly enough to shatter any hold her previous life may have exerted on her. She had been discarded by the man who had pursued her for six years, fathered her daughter, and seemingly adored her for much of their time together. The person she was closest to in the world—her brother George—had been executed on the most hideous and shameful of charges. The rest of her family, as far as we can tell, had either abandoned her or—as Anne believed of her mother–was awash with despair and grief over what was happening. Still recovering from a miscarriage, her body and mind undoubtedly assaulted by hormonal changes and unstable moods, she had been sent to prison on absurd, concocted charges, and “cared for” there by women who were hostile spies. She knew she would never see her daughter Elizabeth again, and—unlike the fictional Anne of Anne of the Thousand Days, who predicts that “Elizabeth will be queen!”—had no hope, after Cranmer’s visit, that her child would ever be anything more than she had seen Mary reduced to: a bastardized ex-princess forced to bow down to any children the new wife might produce for Henry. She had been given reason to hope that she would be allowed to live, only to have those hopes crushed at her sentencing. In a sense, she had already been through dozens of dyings. Nothing was left but the withered skin of her old life, which she was ready to shed. As she mounted the scaffold, wearing a role of dark damask (black in some reports, grey in others) trimmed with white fur, with a red kirtle (petticoat) underneath—red being the liturgical color of Catholic martyrdom—political and national affiliations continued, as they had through her reign and would for centuries to come–to shape the descriptions of her appearance and behavior. To an author of the Spanish Chronicle, she exhibited “a devilish spirit.” A Portuguese witness who had snuck in despite the ban on “strangers”, wrote that “never had she looked so beautiful.” An imperialist observer described her as “feeble and stupefied” (which would be understandable, and not incompatible with her looking beautiful as well.) Wriothesley says she showed “a goodly smiling countenance.” French de Carles commented on the beauty of her complexion, pure and clear as though cleansed by all the suffering. For all, the spectacle of a queen, wearing the white ermine of her role, mounting the stairs to the scaffold, was unnerving.

As she mounted the scaffold, wearing a role of dark damask (black in some reports, grey in others) trimmed with white fur, with a red kirtle (petticoat) underneath—red being the liturgical color of Catholic martyrdom—political and national affiliations continued, as they had through her reign and would for centuries to come–to shape the descriptions of her appearance and behavior. To an author of the Spanish Chronicle, she exhibited “a devilish spirit.” A Portuguese witness who had snuck in despite the ban on “strangers”, wrote that “never had she looked so beautiful.” An imperialist observer described her as “feeble and stupefied” (which would be understandable, and not incompatible with her looking beautiful as well.) Wriothesley says she showed “a goodly smiling countenance.” French de Carles commented on the beauty of her complexion, pure and clear as though cleansed by all the suffering. For all, the spectacle of a queen, wearing the white ermine of her role, mounting the stairs to the scaffold, was unnerving. Unlike her trial speech and her “last letter,” Anne’s remarks on the scaffold made the more conventional bows to the goodness and mercy of the King—in this highly public context, it was virtually required, if only to prevent any retribution against surviving relatives—and asked the people to pray for her. She did not admit to guilt for the offenses with which she was charged or accuse the judges of malice, but did make reference to the “cruel law of the land by which I die.” By now, the four young ladies who had accompanied her to the scaffold (clearly not the hostile spies that had lived with her in the Tower, but others, more intimate with her, who she had been allowed to have with her in these last moments) were weeping. Anne, having helped them take off her robe—an act that in itself must have demanded great composure and courage—“appeared dazed” as he kneeled down, modestly covering her feet with her dress, and asked the executioner to remove her coif, lest it interfere with his stroke. The executioner realized that she was afraid of the pain of an impeded blow; she kept looking around her, her hand on her coif, anticipating the moment. Clearly “distressed” at the task he was to perform, he told her that he would wait until she gave the signal. “With a fervent spirit” she began to pray, and the Portuguese contingent, unable to bear it, huddled together and knelt down against the scaffold, wailing loudly.

Unlike her trial speech and her “last letter,” Anne’s remarks on the scaffold made the more conventional bows to the goodness and mercy of the King—in this highly public context, it was virtually required, if only to prevent any retribution against surviving relatives—and asked the people to pray for her. She did not admit to guilt for the offenses with which she was charged or accuse the judges of malice, but did make reference to the “cruel law of the land by which I die.” By now, the four young ladies who had accompanied her to the scaffold (clearly not the hostile spies that had lived with her in the Tower, but others, more intimate with her, who she had been allowed to have with her in these last moments) were weeping. Anne, having helped them take off her robe—an act that in itself must have demanded great composure and courage—“appeared dazed” as he kneeled down, modestly covering her feet with her dress, and asked the executioner to remove her coif, lest it interfere with his stroke. The executioner realized that she was afraid of the pain of an impeded blow; she kept looking around her, her hand on her coif, anticipating the moment. Clearly “distressed” at the task he was to perform, he told her that he would wait until she gave the signal. “With a fervent spirit” she began to pray, and the Portuguese contingent, unable to bear it, huddled together and knelt down against the scaffold, wailing loudly. Anne gave the signal. But either the executioner or someone else in charge had devised a scheme to distract Anne at the last moment, so the fatal blow would come when she wasn’t expecting it; he turned toward the scaffold steps and called for the sword, and when Anne blindly turned her head in that direction, he brought the sword down from the other side and swiftly “divided her neck at a blow.” As these things went—others had died only after multiple clumsy hackings—it was an easy death: if the naturalist Lewis Thomas has it right, it was far easier than her weeks of suffering in the Tower: “Pain, “ he writes, is useful for avoidance, for getting away when there’s time to get away, but when it is end game, and no way back, pain is likely to be turned off, and the mechanisms for this are wonderfully precise and quick. If I had to design an ecosystem in which creatures had to live off each other and in which dying was an indispensable part of living, I could not think of a better way to manage.” He quotes Montaigne, who nearly died in a riding accident and later described the “letting go” that he experienced at what could have easily been the very end:

Anne gave the signal. But either the executioner or someone else in charge had devised a scheme to distract Anne at the last moment, so the fatal blow would come when she wasn’t expecting it; he turned toward the scaffold steps and called for the sword, and when Anne blindly turned her head in that direction, he brought the sword down from the other side and swiftly “divided her neck at a blow.” As these things went—others had died only after multiple clumsy hackings—it was an easy death: if the naturalist Lewis Thomas has it right, it was far easier than her weeks of suffering in the Tower: “Pain, “ he writes, is useful for avoidance, for getting away when there’s time to get away, but when it is end game, and no way back, pain is likely to be turned off, and the mechanisms for this are wonderfully precise and quick. If I had to design an ecosystem in which creatures had to live off each other and in which dying was an indispensable part of living, I could not think of a better way to manage.” He quotes Montaigne, who nearly died in a riding accident and later described the “letting go” that he experienced at what could have easily been the very end:

Purchase The Creation of Anne Boleyn: A New Look at England's Most Notorious Queen (US)

Purchase The Creation of Anne Boleyn: A New Look at England's Most Notorious Queen (US)